So, this blog has a loooooong backlog of stuff I wanted to talk about but I didn’t. Old stuff, like, one year old or more. Alas, I cannot hope to make a complete post on all that, but I don’t want to let it rot. Let’s do a bit of quick catching up:

- Bird blood on our hands. In 2019 a couple of papers pointed directly the fingers at humans for the extinction of the great auk and the Carolina parakeet, two once-widespread, iconic species of birds that went extinct in the XIX century. Both papers analyzed paleogenomes (is it right to use the ‘paleo’ prefix when it’s a couple centuries ago?) and found out that both species populations had a vibrant genetic diversity until their numbers fell abruptly to zero. Which means: no, they weren’t already fragile, declining species that we gently pushed off a cliff they would have met anyway. We systematically exterminated two robust, healthy bird species in the space of a few decades or centuries. Not exactly unexpected, but now there’s more proof.

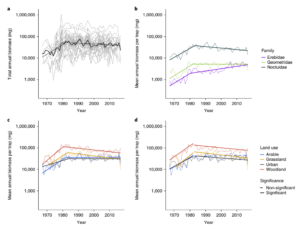

- Butterflies that we will never know. In Singapore, 46% of the butterfly species disappeared (locally) in a mere 160 years, according to a paper of February 2020. Interestingly enough, the study accounts for extirpations of undetected species, using a model. I’m in no position to comment on the math, but the very idea is intriguing and melancholic: about a hundred of species would have gone extinct before we ever discovered them. Of these, some could have well been endemic species: ghosts, of which now we have nothing else than numbers in a statistical analysis. “14.9% of the species discovered before 1900 also were extirpated before 1900. These high early observed extirpation rates, during a period where many species remained to be discovered, suggest that a high number of species were never detected before they were extirpated”

The Karoo Basin, in South Africa, where the best deposits on terrestrial end-Permian/early-Triassic fauna are preserved. - A tale of two end-Permians. Discerning a single event that happened 252 millions of years ago is incredibly hard; discerning a complex interplay of events even harder. Compared to the relative simplicity of the Chicxulub impact, the Permian extinction is a maddening puzzle, muddled by its remoteness in time. There were always hints of multiple extinction events or at least multiple “hits” that led to the Permian catastrophe, but now a paper of March 2020 seems to imply that the extinction on the sea was different from the extinction on the land. It seems that whatever happened on the continents, leading to the demise of most terrestrial fauna and the temporary dominance of Lystrosaurus, happened 300.000 years before the extinction in the oceans: “Instead of the currently favored paradigm of calamitous and globally synchronous turnover in ecosystems, the reported terrestrial turnover in Gondwana occurred hundreds of thousands of years before the marine one and, therefore, marine and terrestrial responses likely had different extinction mechanisms.“. We have to see if and how it will be confirmed, but if so, it seems that the end-Permian extinction is truly two extinctions, above and below water. It will be extremely interesting to grasp how did one influence the other, and how does it translate to our current situation.

- Innocent volcano. In January 2020, Pincelli Hull and coworkers put another nail in the coffin of the volcanic hypothesis for the K/T extinction. The K/T event has the distinction of having two competing or possibly synergic explanations: the well known Chicxulub asteroid impact, and the Deccan traps, a major volcanic event. For decades scientists have fought on what of these events was most important, and even if the impact seemed more and more clearly the culprit, the Deccan enthusiasts didn’t lose their grip. However, if the study is correct, it seems that 1)Deccan outgassing isn’t chronologically correlated to the extinction, but the impact is, and 2)the Deccan volcanism simply wasn’t generating enough gas to trigger an extinction, since similar events didn’t alter the biosphere so much. Another paper a few months later even argued that, if the Deccan volcanism had any effect, it was mitigating the extinction effects.