The Copernican Principle states that we are not privileged observers of the Universe. It is a restatement of the mediocrity principle: there is nothing exceptional about us, about the planet, about our history and so on.

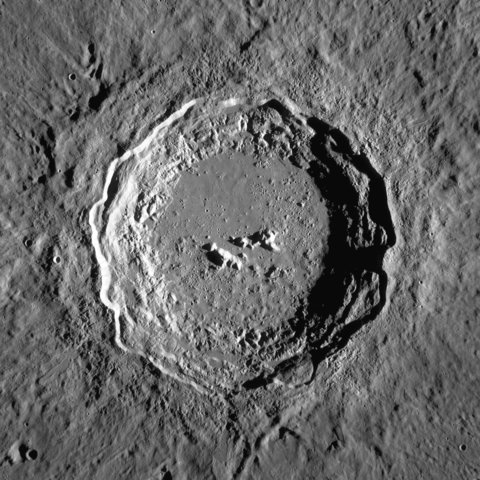

Copernicus is also the name of one of the most prominent and iconic lunar craters, testimony of a massive impact roughly 800 million years old. And while impacts are, per se, relatively common events -one needs only to look at the Moon to see how many happened in the history of the Solar Systems, not all impacts are the same. And some, maybe, are exceptional: so much to make our own history exceptional.

A new paper by the Expedition 364 to the Chicxulub crater has compared the actual geological makeup of the crater to various impact simulations and found something interesting. Most asteroid impacts are oblique, following highly inclined trajectories:

Only one quarter of impacts occur at angles between 60∘ and the vertical and only 1 in 15 impacts is steeper than 75∘.

But, once again, Chicxulub is exceptional. It seems it most resembles craters from steep impacts, about 45-60 degrees. The Chicxulub impactor was steep but not quite vertical hit, zooming right on Earth from the north-east:

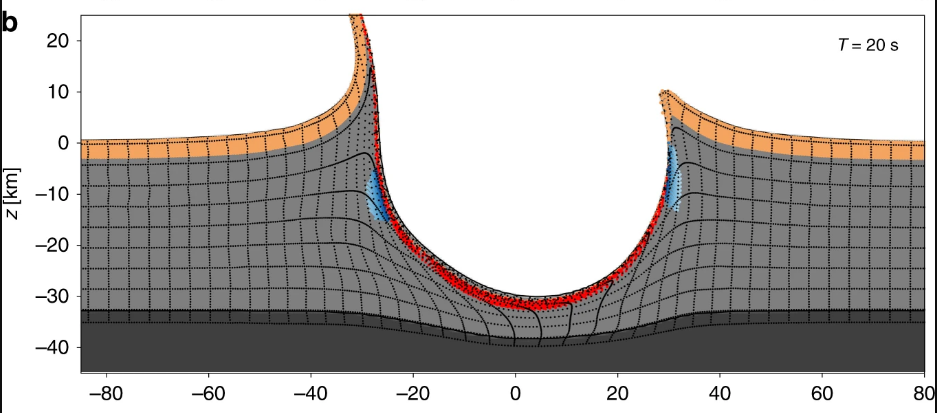

Comparison of these observations with our simulation results suggests that the observed configuration is most similar to the 60∘ impact simulations (or possibly the 45∘ impact simulation at 20 km/s; Fig. 5).

And this was very bad news for the end of the Cretaceous, because they are exactly the conditions that lead to maximum disaster:

Impacts that occur at a steep angle of incidence are more efficient at excavating material and driving open a large cavity in the crust than shallow incidence impacts5,19. Our preferred impact angle of ca. 60° is close to the most efficient, vertical scenario[…]

Impact angle has an important influence on the mass of sedimentary target rocks vaporised by the Chicxulub impact37. […] a trajectory angle of 30–60° constitutes the worst-case scenario for the high-speed ejection of CO2 and sulfur by the Chicxulub impact37. At this range of impact angles, the ejected mass of CO2 is a factor of two-to-three times greater than in a vertical impact and approximately an order of magnitude greater than a very shallow-angle (15∘) scenario37. An absence of evaporites in the IODP-ICDP Expedition 364 drill core is consistent with highly efficient vaporisation of sedimentary rocks at Chicxulub27. Our simulations therefore suggest that the Chicxulub impact produced a near-symmetric distribution of ejecta and was among the worst-case scenarios for the lethality of the impact by the production of climate-changing gases.

So much for the Copernican principle, this further reinforces that the Phanerozoic history is punctuated by improbable events. A giant 10-20 km asteroid such as the Chicxulub impactor hits every few hundred million years. We know of no other impact causing a mass extinction. And Chicxulub happened in the worst possible spot (a shallow sea with bottom rocks rich in sulfur and carbon), in the worst possible moment (terrestrial ecosystems dominated by very large -and thus vulnerable- vertebrates; Chicxulub would have been far less important in the Cambrian or the Silurian!) and, now we know, probably with the worst possible geometry.

Here it is, from the paper: in twenty second, a 30-km deep wound was dug, and vaporized rock was thrown beyond 20 km high in the sky. We are now on Earth because of this event. If the asteroid were a few minutes early, a few minutes late, a few hundred km somewhere else, the history of life would have been completely different. Sometimes the Copernican principle is a principle, not a law. It is a useful guidance, but after all, it would be very weird if no rare, strange events at all happened. We are all improbable ashes of a fateful day that started 66 millions of years ago and still has not ended.

The paper is: Collins, G.S., Patel, N., Davison, T.M. et al. A steeply-inclined trajectory for the Chicxulub impact. Nat Commun 11, 1480 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15269-x